Uncle Bob's Advice on Stability and Abstractions

Published: December 13, 2025

Have you ever worked on a codebase where changing one module triggers a cascade of changes across the entire system? Or where circular dependencies make it nearly impossible to understand which component is responsible for what?

Uncle Bob's Clean Code series addresses these issues with some fundamental principles for managing dependencies in software systems.

In this short article, we'll discuss the incoming and outgoing dependencies of our software, and classify our components as stable or unstable. Then, we'll learn that stable component should be more abstract, whereas unstable components can remain concrete.

Stable vs Unstable Components

Let's imagine you built a small library for parsing CSV files. At first, only your team uses it - it's relatively unstable. You can make breaking changes without too much hassle.

But then, you open-source it and it suddenly becomes super popular. Now thousands of projects depend on it, which makes it very stable. It's stable because you cannot afford to easily make breaking changes to it anymore.

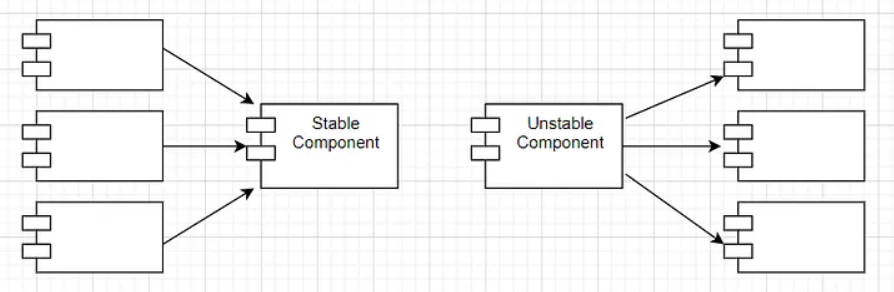

So, we can say that a component is stable if it has many components depending on it, while depending on few others itself. On the other hand, an unstable component has many efferent dependencies.

According to Uncle Bob's Stable Dependencies Principle,

a component should only depend on components that are more stable than itself.

For instance, for your CSV parser library with thousands of users, it's ok to depend on a well-established date/time library which is even more popular. On the other hand, it would be a bad idea to add a dependency on a small utility library that is still evolving rapidly.

Abstract vs Concrete Components

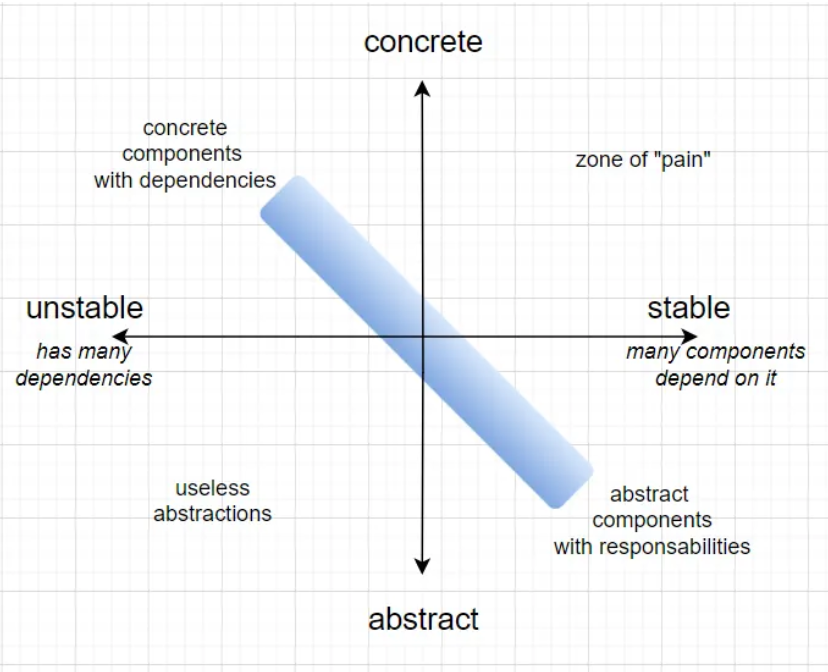

Similar to stability, abstraction is not "boolean" either: A component does not have to be either abstract or concrete. The more abstract classes and interfaces a component has (compared to the total number of public classes), the more abstract it is.

The Stable Abstractions Principle tells us that

the more stable a component is, the more abstract it should be.

Simply put, our popular CSV parser with a lot of users should be designed with abstraction in mind. This will allow us to further extend it without introducing breaking changes. Our CSV parser is stable and abstract!

Let's imagine we also have a UI application that fetches data from multiple backend services and displays it to the user. Most probably, this application is going to have many outgoing dependencies.

Moreover, it will enable the users to perform some operations that are very specific to our system. Therefore, we can say that our UI application is unstable and concrete.

If we have a component that is unstable (few others depend on it & it has many other dependencies), there is no point in keeping it abstract - it'll be useless.

On the other hand, a component that's stable (other modules depend on it) needs to be abstract - otherwise maintaining without breaking users will be painful.

Consequently, we have to keep the proportions between stability and abstraction, aiming for the blue area of the graph.

Takeaways

These principles might sound theoretical, but they've changed how I approach component design.

It's easy to go on autopilot (or copilot) when building new features - creating abstractions "just in case" or avoiding them entirely. Understanding stability and abstraction helps us make intentional decisions instead.

Next time you're designing a component, ask yourself: How stable is this? How stable should it be? The answers will guide you toward the right level of abstraction - not too much, not too little.